PUBLIC SPACE:

CONTINUITIES AND DISCONTINUITIES

The concentration of the country's heaviest industry in Elefsina altered both the inland and the coastal landscape of the city.

The initial phase of Elefsina’s industrialization saw a peculiar landscape, in which agricultural economy coexisted with industry. Farmers sheared their sheep by the sea, right next the smokestacks of TITAN; large vegetable gardens in central points around the city supplied the central farmers’ market at Rentis.

Such contradictory images spanned the history of Elefsina’s public space well until the 1960s, before gradually fading from view in the late 1970s, when industrial and port facilities began taking over larger tracts of land.

Elefsina was turned into a coastal city without a beach. Support for public spaces became part of municipal initiatives only from the late 1970s onwards.

It used to be great back in those days; it saddens me that my children never got to know Elefsina as it used to be. Elefsina was done after 1970; I’m talking about the beach and its surrounding areas.

MICHALIS MITROMELETIS

EXPROPRIATIONS

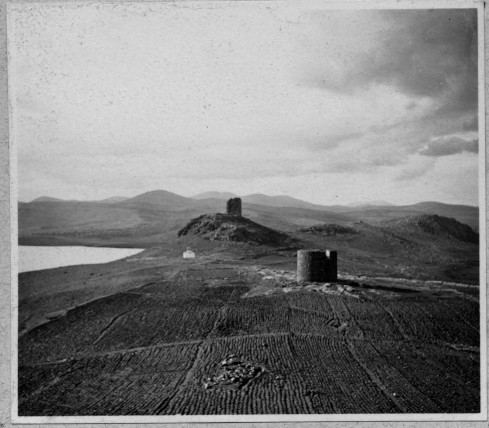

Elefsina meets industry as quarries gradually devour the mountain at Vrachakia, lands and houses are expropriated along the sea, and the coast itself is backfilled with soil. The landscape of the city is altered, and the vital space of its residents decreases as factories surround Elefsina and, in a way, delineate its boundaries.

The first attempt to establish an urban plan for Elefsina was made in 1877. The plan itself demonstrates the intention of the Greek state to separate the land from the sea by creating an artificial beachfront whose purpose was to lay the groundwork for the installation of large industries in the area.

It wasn’t by chance that the TITAN factory was constructed between the sea and the hills. The quarries bore tunnels in the hills, extracted raw materials and converted them into cement. Afterwards, the products were loaded on ships through the private seaport built as an annex to the factory.

The use of tons of dynamite catapulted rocks, soil, and fragments of ancient pottery and buildings into the sky on a daily basis, as local residents scurried inside their homes when a voice cried: “Varda fournelo!” (Fire in the hole!).

Next to the facilities of TITAN, children played war among ancient tombs. The game stopped when the quarries destroyed their hiding places and their toys were broken by the explosions.

One time, we left behind my kite and it was smashed by a rock. My kite, I had crafted it myself, and a rock dropped down and smashed it. [...] I knew it was an explosive, but I never expected a rock to fall and strike my kite.

THODORIS KOUNELES

One of the Symiots’ neighborhoods was developed at Vrachakia and accommodated families that worked at the factory of TITAN. Many houses were built on the hillside, which served as a passage to the sea for the residents of Upper Elefsina.

When the quarry began to "eat up" the hill, besides the Symiots who lost their homes, many inland residents of Elefsina also lost their access to the sea.

People crossed the mountain through a footpath to go swimming, because there was no other way to get here. There was a road at PYRKAL, but it was too far.

THODORIS KOUNELES

Mining activity and explosions grew in intensity and frequency, and the living space of the neighborhood shrunk significantly. TITAN expropriated the homes of Symiots during the period of the military junta (1967-1974), forcing them to leave. The dictatorship was not a good period for protesting or pursuing legal actions before the courts.