The issue of health in the case of cities with extensive pollution or in relation to work at factories and other industries is a relatively recent topic of discussion. Issues related to the health of the local population, the reproductive health of women, and diseases which are detected in higher rates in Elefsina compared to other cities have been making headlines for years. The initiatives against pollution are fairly recent and coincide with the period of Elefsina’s partial deindustrialization.

The same applies for health within the factories. Occupational diseases associated with industry, such as pneumoconiosis, bronchopulmonary disorders, and skin disorders, were widespread in the area.

This is especially the case with the factory of TITAN, which has been incriminated for lung diseases developed among workers and residents of Elefsina, which the locals refer to as "cement coniosis". The installation of the first electrostatic furnace filter in 1961 and the use of synthetic fibers in bag filters led to the drastic reduction of dust emissions, but not until much later, during the 1970s.

In Europe, the gradual process of enacting legal controls for work accidents, occupational health, and child labor took place in the late 19th century. In Greece, occupational health and medicine were formally established in the period from 1911 to 1914. The government of Eleftherios Venizelos passed various laws regarding the health of workers, the employment of minors, health and safety in the workplace, laboratories, shops, and other settings, along with the health of workers and employees of industrial and artisan factories and laboratories of any type.

Law 1568 regarding the "Health and Safety of Employees" was passed in 1958, followed by the presidential decree 213/86, which formally established the medical specialty of "Occupational Medicine". The consolidation of health and safety in the workplace as a labour right entails obligations for employers to ensure health measures, the avoidance of accidents, and the payment of healthcare benefits and compensation in the event of an accident.

Work accidents were directly associated with everyday life in Elefsina. The rates of morbidity and mortality in the city have always been higher in comparison to the rest of Greece, because a large segment of Elefsina’s population worked in some of the country’s largest industries clustered in the area. On that account, the city always had significantly higher needs in terms of healthcare.

For the people of Elefsina, the sound of an ambulance's siren meant that a worker had been hurt in one of the city’s factories. Despite its size, Elefsina was left for many years without any public health infrastructure, except for a few private clinics, whose limited capacity made them incapable of handling the health needs of the city.

The prevalent working conditions did not ensure the physical safety of workers. Safety measures were nonexistent, which is why they were so often among the primary demands of workers. Accidents varied according to the period. In the early days of industrialization, safety measures were minimal and the working and living conditions of workers were very harsh, because of the extreme poverty in the region.

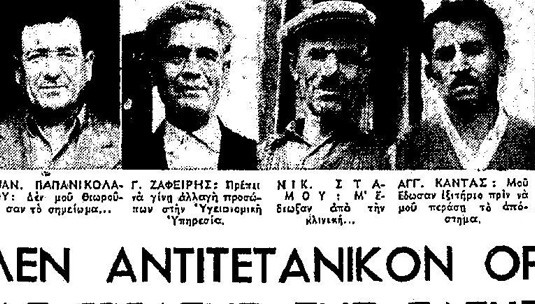

For many decades, the workers at the factories of Elefsina were forced to live in insecurity, fearing that they would be laid off in the case of an accident. If they were left “crippled” instead, they would never be able to work again. The acknowledgement of a work accident by the industry was no easy task; employers would not take responsibility for the consequences suffered by workers due to working conditions, deadly or not. At the same time, the factories systematically treated all accidents as results of personal responsibility of workers.

Accident victims are blamed for 95% of the accidents that they suffer. Yeah, human error. Well, being a trade unionist, I am not adhering to this view, because a random accident is having a roof falling on your head; this is a random thing. In addition, if you work here and you are walking, and some other guy is operating a crane that’s hoisting a load and he hits you, you still say that it’s random, because they claim it’s the other guy’s fault. Anyway…

THYMIOS ANDREADIS

A typical example was the "safe work prize" paid to all workers at TITAN, which was suspended if any person suffered an accident. This, on the one hand, compelled workers to comply with all safety measures applicable on the factory grounds, but it also marked the limits of the company’s liability.

NON-ACCIDENT

ALLOWANCE

Employers often attempted to silence incidents by offering employment positions or financial and other considerations to the families of victims. This is frequently reported in the narrations of workers during the initial period of industrialization, who, while being involved in accidents faced the dilemma of "saving" their job or themselves for fear of dismissal.

This one time I fell (because I didn’t want to be thrown out of the port), I slipped on the plank and fell into the sea. And I wouldn’t let go off the sack, since, otherwise, it would be lost in the sea. Three of them jumped on me and struggled to take my hands off the sack and carry me out. And the foreman asked me: "Why the hell didn’t you just drop the sack?” [To which I replied:] “Would you take me back to work tomorrow, if I did?” That’s what it had come to.

MALLIOS ANASTASIOS | INDUSTRIAL MEMORIES (2006)

The acknowledgement of work accidents and their prevention were included in the demands of workers’ struggles after many losses, both fatal and non-fatal, of people working in the factories.

Based on the approach of health and safety in the factories, both male and female workers had to be dressed in special clothes. Footwear was equally important in many cases: in TITAN, shoes were heavy and puncture-resistant to protect against injuries caused by falling objects. In PYRKAL, shoes had to be designed with special insulation. Male and female workers at PYRKAL were required to leave metal objects and jewelry out in their lockers, because such items could carry electric charges. Women were also required to wear special underwear for the same reason.

Although work accidents are now reduced compared to the early days of industrialization, they still occur at the factories of Elefsina and in other places. Their acknowledgment and prevention remain among the demands of workers’ struggles to this day.

In 1996, one century after the erection of the city’s first chimney, Thriasio Hospital began its operation. The inscription on the marble plaque placed by municipal and state authorities at the hospital’s opening ceremony reads: "BUILD BY THE PEOPLE AND THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT". The hospital was envisioned by the residents of Elefsina, its industrial trade unions, and its mayor, Michalis Leventis. The development of the hospital was decided during the first year of his term, in 1976.

Other than the workers of Elefsina who were employed at the factories, work accidents still remain a topic of concern for the entire city because of the type of industrial facilities which are still operating in the region. The refineries of Hellenic Petroleum (formerly PETROLA), owned by the Latsis Group, are adjacent to–they are only a few meters apart–with the munitions factory of PYRKAL. The immediate proximity of the plants of PETROGAZ and Chalyvourgiki also presents a danger.

It is not by chance that Elefsina, as well as the wider region of West Attica, are included in the Seveso directive. A large-scale accident in one of the factories in the areas of Elefsina and Thriasian Plain could potentially become fatal and catastrophic not only for the city, but also for the region at large. This directive was named after the accident that occurred in the Italian city of the same name in 1976, when poisonous gases were released into the air from a plant and caused the death of thousands.

This directive specifies the preventive measures which must be implemented by the industries in the area, such as, for example, the prohibition of storing fuel, explosives, and hazardous chemical substances in excess of a specified quantity, an organized plan for the management of the consequences of a disaster, which must also provide for the quickest possible response by all competent state entities for the purpose of containing the impact (Technological Accident Response Plan, SATAME in Greek). Nevertheless, the close relationship between state and industry does not ensure that the latter will comply with the directive's instructions.