PUBLIC SPACE

Absolute silence reigns in Elefsina at this hour of the evening. Suddenly, the whistling of the horn at the cement factory tears the silence spreading over the city apart. “It is five p.m. in Greece” announces the radio at the coffeehouse. Its owner jumps up from his chair, as workers begin streaming out of the factories. The mass of bicycles is a special sight to behold. There is perhaps no other city in Greece with so many bicycles. A happy buzz can be heard rising from the whole city. Elefsina begins to live and move. It is the workers who give it life and motion.

AVGI | 18.01.1959

What happens in Elefsina outside the factories? Where do its people go and live their lives when they aren’t working? How much public space within the city has been left untouched by industry?

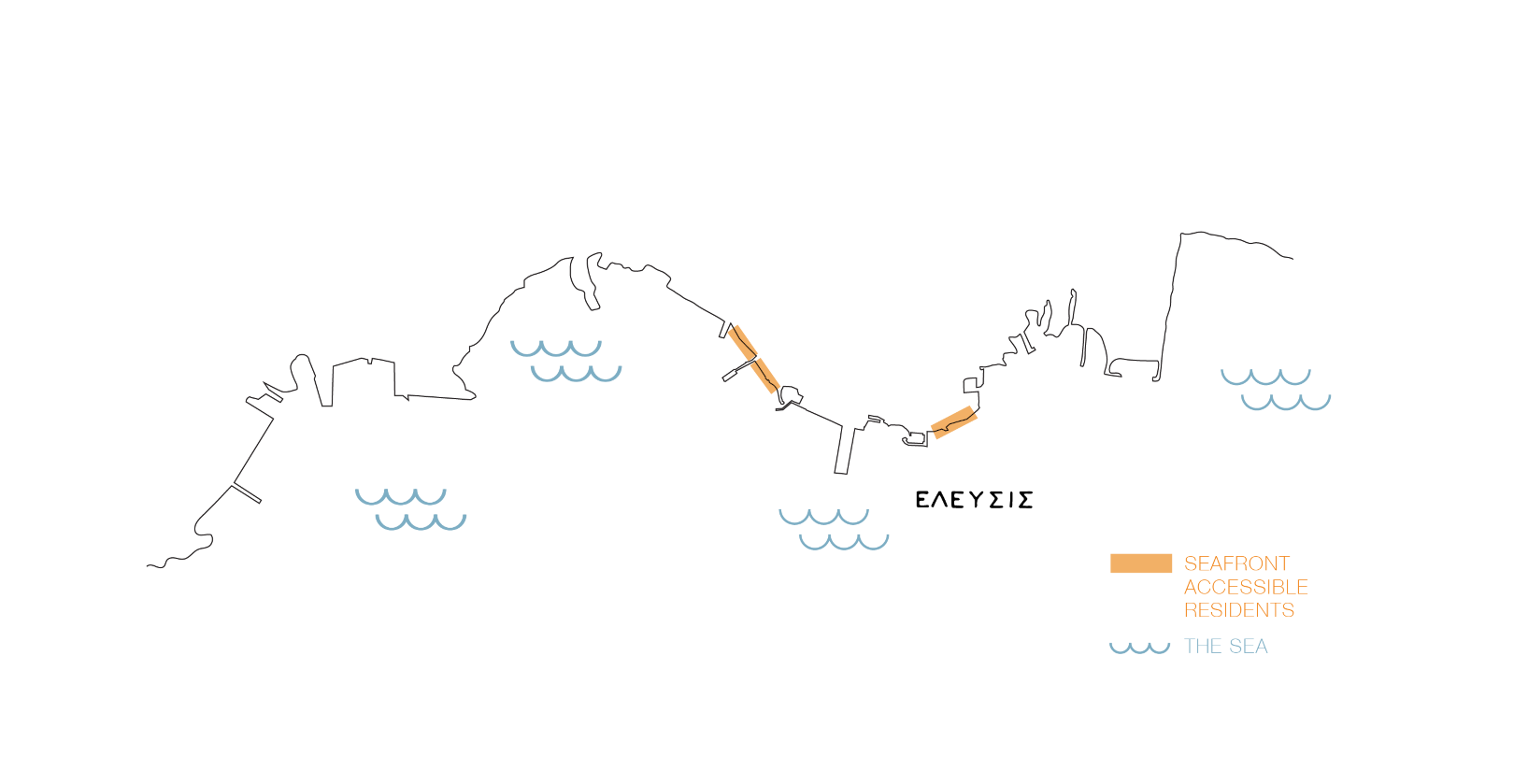

The beachfront, Nikolaidou Street, and the railroad tracks are lines that cross Elefsina and emphasize the strong contradictions pervading the city: sea and land, industrial and urban landscape, ancient and modern, upper and lower city. However, there are also lines that reappear in the various stories that residents narrate about their city, demarcating the spaces between and beyond the factories.

The stories surrounding the beachfront reflect continuities and discontinuities related to the access of locals to the beach or lack thereof. The trip to the beach on foot, by bicycle, or car is interrupted by the gate of TITAN.

The factory literally cuts the city off from its inland areas. The public road crossing the facilities of TITAN, demarcated by a bar gate at the entrance from the city and by an automatic sliding metal gate at the exit towards Vrachakia and Vlycha, is a mysterious passage for both locals and passersby–it is, according to the term popularized by the anthropologist Marc Augé, a non-place. This place is perceived by the locals as having been cut off and appears to have no particular identity or historical quality in their stories.

Both locals and passersby stop at the bar gate. When the factory was still operating, it was forbidden to go through during the hours when the products were transported. Many people weren’t even aware that they could go through the gate. The image of a rising bar in the middle of the road had a deterrent effect for passersby.

In any case, the experience between those who worked inside TITAN and older residents at the workers’ dwellings located within the factory premises differed.

We were born and raised in the dwellings built by TITAN for workers; they were called TITAN dwellings or just chambers, because they consisted only of a large chamber and a smaller room. Our lives were inextricably linked with the factory: we had to cross the factory grounds to go to our houses and if we were to exit our houses to go to school, or anywhere else, we still had to cross the factory grounds.

ARGIRO ORFANOUDAKI | EXCERPT FROM “DEMECHANIZED INDUSTRY”

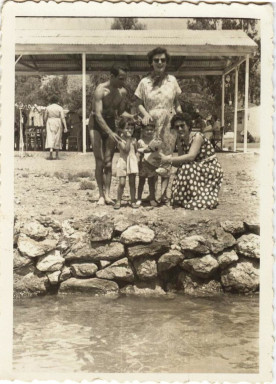

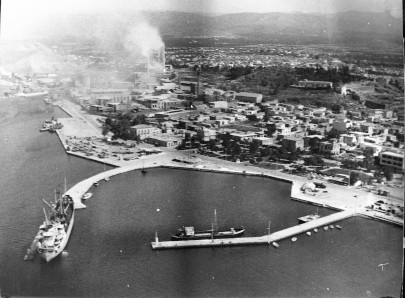

Although the beachfront of Elefsina was filled up with factories, it remained a vibrant place where the land and the sea created of zone of intense activity: sloops, service boats, fishboats, factory docks, machinery, timber, raw materials, and merchandise on dry land were the elements composing the scenery of this coastal zone.

This picture was enriched by people "at work" or "on break", children playing amidst the cargoes of raw materials and merchandise, young and old swimmers in the bays created by the embankments, and passersby taking strolls.

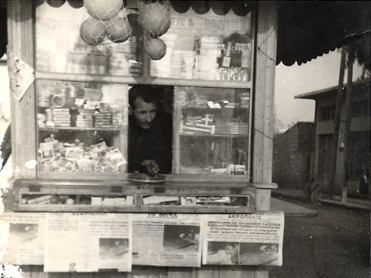

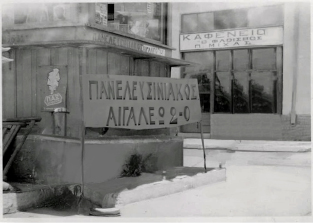

There are familiar landmarks registered on the area’s invisible map. Prominent among them stand the refreshment bar at Fonias, the open-air cinema, and the kiosk at Nikolaidou Street.

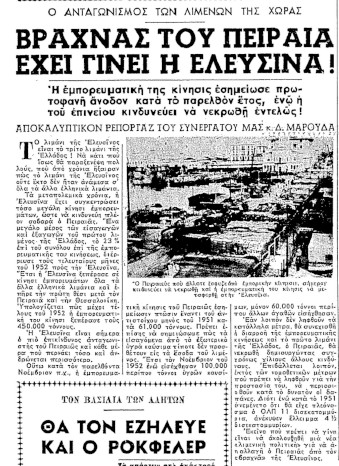

Elefsina has become a thorn in the side of Piraeus. The mobility and transport of commodities went up during the past year in Elefsina, while the harbor of Piraeus is at risk of dying away!

EMPROS | 08.02.1953

Due to the emergence of more specialized products (steel mills, refineries, shipyards) after World War II, it became necessary to develop the port further and allow factories to construct their own private docks.

Up until that time, the access to the coastline was split between points going through the private docks of factories and their loading sites.

From 1950 to 1970, the coastline was taken over by larger-scale manufacturing plants, fit for heavier production, compared to the previous 75-year period (1875-1950).

During the third phase of Elefsina’s industrialization, the entire coast of the gulf of Elefsina was occupied by factories and port facilities.

The length of the coast is approximately thirteen kilometers from the estuary of Sarantapotamos in the east to Loutropyrgos in the west as the crow flies. Twelve out of these thirteen kilometers remained inaccessible to the residents of Elefsina, because they had been absorbed by factories and port facilities.

As a consequence, from the 1970s, access to the already fragmented pathways to the coast gradually became more and more difficult and dangerous, until it was eventually prohibited.

THE FILM “ELEFSINA”

BY T. PAPAGIANNIDIS

THE BEACH

HAS VALUE

EVERYWHERE

ON EARTH